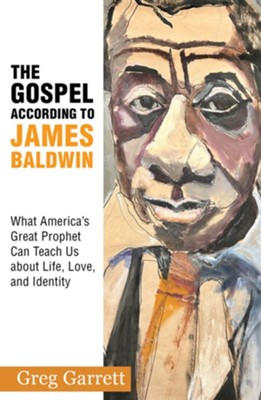

BOOK REVIEW: Greg Garrett amplifies James Baldwin’s prophetic call from ‘Go Tell It on the Mountain’ to ‘The Welcome Table’

The author and educator Greg Garrett has been teaching the works of James Baldwin for many years in his courses at Baylor—and it took those decades of reflection and dialogue with students before Greg could finally give birth to his newest book, The Gospel According to James Baldwin.

One milestone that helped Greg was a major grant from the Baugh Foundation to study how American media has shaped popular racial attitudes—what Greg calls “racial mythologies.” The foundation’s financial support helped to fuel his wide-ranging research on related issues in the U.S. and around the world.

“Racial mythologies have been deeply embedded in American life, from film to legal codes to theology to popular and material culture,” Greg said at the time the Baugh grant was announced. “Any myth that denies a person her or his humanity has to be excavated, examined and repented. So often, we are unconscious of the degree to which those mythologies are operating and even defining us.”

Another milestone that refreshed Greg’s life-long interest in Baldwin’s life and work was the 2017 acquisition of “30 linear feet” of Baldwin’s papers, manuscripts, notes and artifacts by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at The New York Public Library.

“This collection at the Schomburg is incredible!” Greg said in our interview about his Baldwin book. “I want to keep learning about—and from—James Baldwin for the rest of my life. So, looking at these manuscripts—especially those about the play, The Welcome Table, that he was working on at the end of his life—allowed me to see how Baldwin kept working on this idea over time. As an Episcopalian, I believe that some relics are holy and, when I was holding a manuscript of The Welcome Table that included the author’s hand-written corrections—well that’s a holy moment, a holy relic.”

“I have to credit the archives with letting me move the closest to Baldwin that I have felt in my life,” Greg said. “And, that was just one of destinations where I got closer to Baldwin. I start and end this new book with descriptions of trips I made to the same Swiss village where Baldwin went at least three times—and I think I’ve uncovered a fourth visit he made later in his life. Walking the same streets in Switzerland that he walked, I felt a deep connection with him—seeing what he saw and looking out across the same valleys he saw as he wrote there.”

‘THE WELCOME TABLE’—A GOOD REASON TO ORDER THIS BOOK

Greg ranks the papers concerning The Welcome Table among the greatest treasures in the Baldwin archive. Baldwin still was working on the play when he died in 1987 at age 63. To Garrett’s knowledge, no one has yet secured the rights to produce a version of that nearly finished draft. And, reading Garrett’s book, perhaps someone will feel moved to do so.

To put it simply: That section in Greg’s book about The Welcome Table is a good reason to buy a copy of his new book, even if you have other works by and about Baldwin on your shelf.

This play, in Garrett’s words, “brought together many of his greatest themes” and “would have been a fitting end to a monumental life. … In most of Baldwin’s work, failures to love sacrificially, failures to love with courage, failures to love in the face of whatever others might say about love, doom characters.” Nevertheless, “even in The Welcome Table, where Baldwin was wrestling with his late-life inclinations about the necessity of love and the irrelevance of labels, we find characters trying to live into the importance of love.”

Greg said, “Throughout his life, he loved the Blues, hymns and spirituals and The Welcome Table connects us all the way back to the era of slavery—and the hope that there is a kingdom we all are working toward.”

ACKNOWLEDGING THE PRIMACY OF LOVE

In the book itself, Greg writes:

To the end of his life, Baldwin spoke of the concept of the Welcome Table, a place where this brotherhood and sisterhood, this kind of love, this kind of unity, might be possible. The concept comes from a spiritual that was also sung in the civil rights era. Its first verse proclaims, “I’m going to sit at the Welcome Table one of these days.” Perhaps just now, I am alone, hungry, sad, lost. But someday, somewhere, there will be a place where I belong. Where I will be seen and known. Where I will be accepted. Where I will be welcome at the feast alongside all my brothers and sisters. One of these days, I’m going to sit at the Welcome Table.

This was an article of faith for Baldwin. If we did not succumb to fear and hatred, if we did not implode from our own divisions, such a thing was attainable.

WHAT ELSE IS IN THIS NEW BOOK?

If you have read this far, you probably are familiar with Baldwin in some way. Perhaps you were assigned to read his books in school—as Professor Garrett does each year with at least one Baldwin book for his classes at Baylor. Perhaps you enjoyed Barry Jenkins’ Oscar-winning 2018 version of Baldwin’s 1974 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk. Perhaps you are old enough that, like me, you followed Baldwin’s provocative literary and film criticism as it flowed through major American media during his prime.

So, you may be asking: Do I need another Baldwin book?

This column is arguing: You do. But let’s be clear on what Greg is offering here to both individual readers who want to reflect on faith and race and culture in America—and to small groups who may want to engage in that kind of timely discussion in their communities.

What he is not attempting in this new book is another exhaustive biography of Baldwin. If that’s what you are seeking, I can recommend the three volumes of Baldwin’s own works collected by Library of America, since Baldwin publicly explored his own life and wisdom across his published works. In effect, he wrote his own autobiography. If you want a substantial biography of Baldwin by a scholar, I can recommend David Leemings’ 1994 biography of Baldwin that’s more than twice the length of Greg’s book. Or, you might consider Princeton scholar Eddie S. Glaude Jr.’s 2020 Begin Again, which also is a lot longer than Greg’s book.

What Greg Garrett has accomplished is what I would describe as a very compelling “magazine-style overview” of crucial themes that Baldwin was trying to convey across the decades that we had him with us on the planet. In other words, Greg has given us a book that everyday readers can jump into without a lot of background reading—and glean some very timely insights.

In chapters on Culture, Faith, Race, Justice, Identity and New Beginnings, Garrett takes us through the broad sweep of Baldwin’s wisdom about how the world desperately needs to confront our collective, selfish and destructive biases—if we hope to have any chance at reconciliation. And, as Baldwin always emphasized: That sentence contains a huge “if.”

Baldwin never was certain that we could collectively attain what he yearned was possible.

JAMES BALDWIN AS A PROPHET FOR OUR TIMES

Greg Garrett is not the first writer to refer to Baldwin as prophetic, but he does argue this case in a fresh and persuasive way in this new book.

“This is something he thought about himself,” Greg said in our interview. “At various points in his life, he wrote that he saw himself as a sort of Jeremiah—and I think that’s a perfect characterization of him. I think of that passage as Jeremiah stands at the temple saying to the people: ‘God will not reward your worship and faithfulness until you treat the marginalized with justice.’

“When we encounter Baldwin today, that’s sort of what it feels like: Being there when a Jeremiah calls out to all of us. And Baldwin’s voice still moves people, if we only listen, if we only read. We are now more than 70 years from Go Tell It on the Mountain and 60 years from The Fire Next Time—and, those books still are read and are moving readers toward the kingdom that Baldwin always was seeking. This is not wisdom lost on a dusty library shelf. This is wisdom people still are encountering today and can wind up living every day of their lives as a result.”