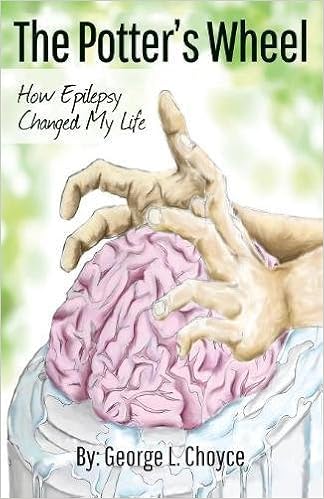

The Rev. George L. Choyce: Excerpt from "The Potter's Wheel: How Epilepsy Changed My Life"

In this excerpt from his new book 'The Potter's Wheel," which tells his story of moving through the stages of grief in dealing with epilepsy, Episcopal priest George Choyce shares insights about the stage of anger.

The Potter's Wheel: How Epilepsy Changed My Life

The Rev. George L. Choyce

Chapter 14

The Cauldron Simmers

Stage II - Anger

Do not be quick to anger, for anger lodges in the bosom of fools. - Ecclesiastes 7:9

Rend your hearts and not your clothing. Return to the Lord, your God, for he is gracious and merciful, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and relents from punishing. Joel 2:13

O merciful Father, who hast taught us in thy holy Word that thou dost not willingly afflict or grieve the children of men: Look with pity upon the sorrows of thy servant for whom our prayers are offered. Remember him, O Lord, in mercy, nourish his soul with patience, comfort him with a sense of thy goodness, lift up thy countenance upon him, and give him peace; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. BCP, p. 831

This journal entry is a fitting lead-in to the anger phase of grief. It helped me cope with my grief on the day I wrote it, knowing that someone else someday would read it in the context of this journal.

By vocation, I am an Episcopal Priest. My "holy" vocation, however, did not bring to a halt what happened deep within the left frontal lobe of my brain; in fact, it might have even caused it. Physiologically, what happened at about eleven o'clock the morning of August 2 was an explosion of sorts - an explosion of blood. For whatever reason, an abnormal cluster of nerves in my brain called a Cavernous Malformation, violently forced blood out in all directions. Under immense pressure, blood splattered throughout a miniscule area of my brain. In other words, deep within my left frontal lobe a tiny area under extreme force pressed outward in all directions resulting in a brain hemorrhage.

The internal bleeding irritated a small section of tissue in my brain, and the neurons in my nervous system misfired and resulted in a seizure. The specific classification of my seizure is called a complex partial seizure. My complex partial seizure, regrettably, took place in the context of a sermon. Some parishioners thought I was pausing for almost two minutes for dramatic effect. No one, except for my associate, talked about the "episode" to me after the service. The subject of seizures is still taboo, even in the twenty-first century.

The word "seizure" is recognizable to most of us. My guess is that most of you reading this picture a seizure in the framework of someone falling down, becoming rigid and shaking uncontrollably. I limited my understanding of a seizure that way before August 2, 2009. My journey has led me to the coherent comprehension that there is a wide range regarding the classification of seizures. There are seizures that run a gamut of simple to complex, brief to long, standing to falling.

In my opinion, and at the risk of sounding rather preachy, we must move past ignorance concerning seizures. It is significant for you to know the medical classifications and descriptions of seizures, which are at the end of this book. Most people recognize the terms "petit mal" and "grand mal," yet these classifications are outmoded and imprecise. (See pages 196-198 in the book for a more complete list.) In addition to this, having an elementary grasp of seizures can remarkably reduce the phobia of seizures.

I should know since people started to avoid me after finding out about my epilepsy as if I were infectious or would "go off" in front of their children or grandchildren. Furthermore, if I were to have a seizure in public, I would embarrass them in public. (This phenomenon is not, by any means, unique to me. Many with epilepsy feel this way.) What makes this so psychologically painful is that some of these people were my friends, key word here being "were." Betrayal and abandonment are not hard-hitting enough words to describe my feelings. As emotional as these feelings are, they are part and parcel of the indispensable steps of the grieving process.

It is not, however, epilepsy alone that evokes these strong passions. Other neurological conditions, from the A of ALS (known as Lou Gehrig's disease) to the Z of Zellweger Syndrome, have some sick stigma attached to them which only serves to magnify the physical pain and emotional turmoil of the medical condition. For instance, it was only after an article of mine was published concerning my new life with epilepsy and how I was desperately trying to regain my vocation as a priest that a colleague of mine wrote in a letter to me about Parkinson's disease what I had written about epilepsy. He too used the words embarrassment, as well as contagious. He too felt abandoned by friends, as well as colleagues. He too had people who did not know how to interact with him even on the surface level when he went public about his Parkinson's.

Can you believe this? Now for just a minute, I ask that you stretch your imaginations. I wonder how many of you have ever undergone this treatment in any type of situation. For those of you living with a disability, I need write no more on your feelings or experiences. That would be beneath patronizing.

For those of you who do not live with a disability, I honestly hope you can tap into an experience, any experience when you felt similar to my colleague with Parkinson's who must feel this way on a daily basis. Have you ever been treated as if you were contagious? Have you ever felt your very presence was an embarrassment? Have you ever been intimidated and anxious about going out in public to do something as simple as shopping? Envision never getting reprieve from the pessimistic way you are treated. I hope you are so ticked off right now that your passion in this anger phase of grief leads you to have a vision to do something about it. I think that this book is how I am responding positively to the passion of anger. The two of us are stronger than one of me.

For me, I ask that you give me something precious of yours - more of your time. It really is that simple, and it really is that hard. Case in point - I know I am slow. The high-powered medication I am on causes me to talk and walk sluggishly, as well as sometimes to even slur my words. Now and again, I stumble. I frequently forget names, as well as some subject we have just discussed. These are the quite common side effects of almost all anti-seizure medications. So is exhaustion. By the way, I have to drink two cups of coffee in the morning simply to function.

It all adds up to the illusion that I am intoxicated if I am unable to have my coffee. This is embarrassing to the onlooker. I wonder what you would think of me if you were that onlooker. What would you think of me if you met me on one of my bad medicine days: sluggish walk, slurred words, and stumbling? A drunken priest, really! It creates guilt by association.

Another case in point - a colleague of mine was on an even more powerful combination of anti-seizure medications for a different medical condition altogether, that he also, from time to time came across as inebriated. Just like my other clergy colleague with Parkinson's, this priest embarrassed them. As if in retaliation, the ultimate insult was to embarrass him by doing an intervention. And later, when it was proven that he did not have an issue with alcohol, his congregation continued to make it so difficult for him to stay on as their Rector that he took retirement disability just so that he would continue to get some form of stipend in order to take care of his family. He and his spouse no longer go to church ... anywhere; neither do his kids!

According to Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, anger is the second stage of the grief. Just as the loss of a loved one is a part of grief, the loss of health is just that - a loss, a loss of something significant in our lives. Loss is loss. Sudden loss of your health is something that others might not grasp as loss; however, when someone guides you by the hand and gently sits you into a chair as if you are a child learning to walk, and you have no memory of the last two minutes, you have not only experienced a seizure, you have experienced a loss. For me, it was not just a loss of health; it was also a loss of dignity. Emotionally, I had lost my self-respect.

"It's a medical condition," you may be thinking. "Why would you lose your self-respect?" you may be asking. For me, the losses were emotional and extremely personal. For me, the losses were my objective reality. I imagine that others who have seizures suffer something like I was feeling on that day, as well as the dull emotions associated with epilepsy in the years to come.

For more information or to order "The Potter's Wheel," click here.